Each submission gets timestamped with EST time and gets a unique identifier

assigned, example:

S10056

I’m an inner-city kid through and through, and if I had listened to all the dissenting voices, I should have been a statistic. I grew up in Newark, New Jersey, surrounded by constant violence during the height of the war on drugs, in a neighborhood full of kids teeming with talent and potential but constantly having to outrun the shadow of hopelessness. I saw so much talent unfulfilled, stifled by the lure of fast money and even faster downfalls.

As a Black male:

And unfortunately, for a number of my friends, these things became realities. I was in the sixth grade when I lost my first friend. Sadly, he wouldn’t be the last.

Fortunately, I had a strong mother who pushed me hard and refused to let me become a statistic. She was fully aware of all the potential pitfalls waiting for me and knew that she had to do whatever was necessary to keep me away from them. At times she worked two jobs so she could provide me with opportunities, like attending summer camps. We didn’t have the means to move from the neighborhood, but she didn’t want the neighborhood to be all I knew. She would always tell me that school was my job because she knew education was the key to opening any locked door that would block possibility.

Growing up, I loved playing with Legos. I could spend hours on the floor, lost in worlds of my own making. I would create and recreate cityscapes, imagining changing my neighborhood from drab and monotonous public housing to something more engaging and hopeful. I vividly recall having a conversation with my mom when I was 10, telling her how cool it would be to play with Legos for a living. It was then that she told me about architecture. It was my lightbulb moment. That’s what I wanted to do!

Academics came easy for me. And because of that, and with the help of financial aid, I went to one of the best schools in Newark: St. Benedict’s Prep. It’s a boy’s private school run by Benedictine monks in the heart of downtown. It’s in the middle of the city, yet so far removed from the harshness outside its doors. My neighborhood was 100% Black, but St. Benedict’s was diverse, with a mixture of students coming in from the suburbs and as far away as South America. From my first time walking the halls, the phrase painted above one doorway—“Whatever hurts my brother hurts me”—struck me as something altogether different and would stick with me throughout my life.

As a 12-year-old seventh grader, I convinced the faculty at St. Benedict’s to let me take the 9th-grade architecture history and drafting class. I received an A, and architecture hooked me. Even though I had never met an architect, I was determined to become one. I was determined to reshape the environment where I grew up to create a better future.

I chose Temple University because it was in Philadelphia, and I wanted to be someplace that felt familiar, someplace that felt like home. Being an architecture student quickly taught me that nothing was familiar to me. Unlike my neighborhood or even the rest of campus, when I crossed the threshold of the architecture school, there were not many familiar faces.

As a Black student in architecture, I carried a considerable weight. I had an honor to uphold. In my first years, the Black students in my class dwindled from 10 to four. But I refusedto be another statistic. I remembered how hard my mom had worked to help me get to that point and how my family was cheering me on (along with my cousin), to be the first college graduates of our generation. So, I buckled down, with work and all, and by the time graduation came, I was one of two Black students in a graduating class of 25.

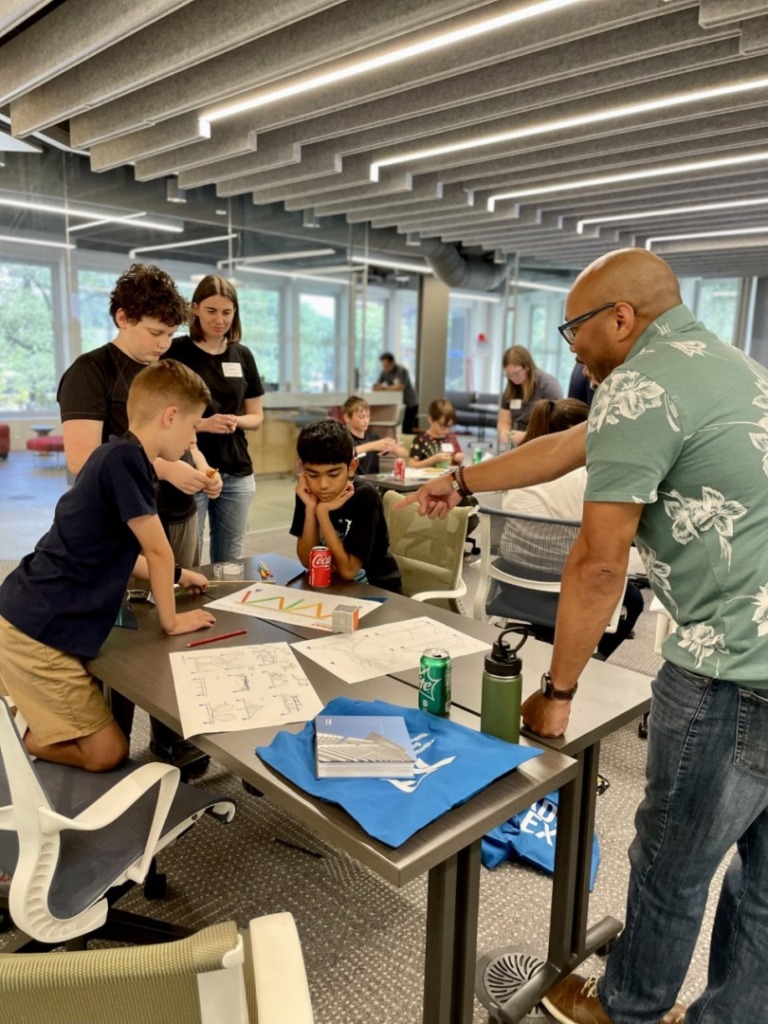

This number is why I push hard to expose the next generation of minorities to this complicated yet amazing profession. They can only aspire to what they’re exposed to. I can’t let equity, diversity, and inclusion become the latest buzzwords that dissipate like the wind when the new it thing comes along. It’s what compelled me to write an article after the killing of George Floyd on camera because I’m Black and an architect. In my work with local organizations, I focus on summer camps and individual mentorship because I’ve experienced firsthand how they can make a difference.

Although I continue to live a dual reality, the two worlds aren’t mutually exclusive—they are interconnected and intertwined. They are both a part of me. I have to be able to bring my whole self to work and just be me. As a Black architect, I’ve often felt the weight of being the representative for my race. I had to outperform everyone else, so those coming behind me would have an open door to walk through and not experience so many bumps on the roller coaster.

Two percent is too few. So I’ll spend the rest of my career advocating and opening doors. And I will make our profession more reflective of the communities and clients we serve.

Brien Graham is a licensed architect and experienced project manager at LPA Design Studios. He is the 2023-2025 AIA Strategic Councilor for Texas, Treasurer for DFW NOMA, and a recent graduate of the inaugural AIA National Leadership Academy, with a passion for providing young students early exposure to architecture.

Each submission gets timestamped with EST time and gets a unique identifier

assigned, example:

S10056

Your ID: S12312312

This notification means your entry was sent successfully to the system for review and processing.

If you have any further questions or comments, reach out to us via the main contact form on the site

Have a great day!

New to NOMA?

Create your account

Already have an account?

Sign in

Not A NOMA Member? Click Here!

Create your account